Initiation of complementary feeding practice and associated factors among mothers having children 6-23 months of age, in Meket Woreda, North Wollo Ethiopia, 2020: a multicenter community-based cross-sectional study

Dejen Getaneh Feleke, Abebu Yasin Tadesse, Ermias Sisay Chanie, Amare Kassaw Wolie, Sheganew Fetene Tassew, Gashaw Mehiret Wubet, Abraham Tsedalu Amare, Tadela Dires, Eshetie Molla Alemu, Melkalem Mamuye Azanaw, Fisha Alebel Gebre Eyesus, Sintayehu Asnakew

Corresponding author: Dejen Getaneh Feleke, Department of Pediatrics and Child Health Nursing, College of Health Sciences Debre Tabor University, Debre Tabor, Ethiopia

Received: 20 Feb 2021 - Accepted: 07 Oct 2021 - Published: 27 Jan 2022

Domain: Public Health Nursing,Child nutrition,Pediatrics (general)

Keywords: Complementary feeding, children, Meket, Ethiopia

©Dejen Getaneh Feleke et al. PAMJ-One Health (ISSN: 2707-2800). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article: Dejen Getaneh Feleke et al. Initiation of complementary feeding practice and associated factors among mothers having children 6-23 months of age, in Meket Woreda, North Wollo Ethiopia, 2020: a multicenter community-based cross-sectional study. PAMJ-One Health. 2022;7:14. [doi: 10.11604/pamj-oh.2022.7.14.28472]

Available online at: https://www.one-health.panafrican-med-journal.com/content/article/7/14/full

Research

Initiation of complementary feeding practice and associated factors among mothers having children 6-23 months of age, in Meket Woreda, North Wollo Ethiopia, 2020: a multicenter community-based cross-sectional study

Initiation of complementary feeding practice and associated factors among mothers having children 6-23 months of age, in Meket Woreda, North Wollo Ethiopia, 2020: a multicenter community-based cross-sectional study

![]() Dejen Getaneh Feleke1,&, Abebu Yasin Tadesse, Ermias Sisay Chanie1, Amare Kassaw Wolie1, Sheganew Fetene Tassew2,

Dejen Getaneh Feleke1,&, Abebu Yasin Tadesse, Ermias Sisay Chanie1, Amare Kassaw Wolie1, Sheganew Fetene Tassew2, ![]() Gashaw Mehiret Wubet3,

Gashaw Mehiret Wubet3, ![]() Abraham Tsedalu Amare4,

Abraham Tsedalu Amare4, ![]() Tadela Dires4, Eshetie Molla Alemu5,

Tadela Dires4, Eshetie Molla Alemu5, ![]() Melkalem Mamuye Azanaw5,

Melkalem Mamuye Azanaw5, ![]() Fisha Alebel Gebre Eyesus6, Sintayehu Asnakew7

Fisha Alebel Gebre Eyesus6, Sintayehu Asnakew7

&Corresponding author

Introduction: improving the infant and young child feeding practices in children aged 0-23 months is critical. It is necessary to improved infant and young child health, nutrition, and development. Over the years, infants and young child feeding policy implementation focused mainly on the promotion of breastfeeding practices while complementary feeding practices. Infant and under-five mortality rates in Ethiopia are 43/1,000 and 55/1,000 live births, respectively. There was limited updated evidence regarding the initiation of complementary feeding and associated factors in the 6-23 months life of children in the study area. objective of this study was to assess the the prevalence of Initiation of complementary feeding practice and its associated factors among mothers with children aged 6-23 months in Meket Woreda 2020.

Methods: the community based quantitative cross-sectional study was conducted among 416 mother-infant pairs of 6-23 months in Meket Woreda, Northwest Ethiopia from March 20-June 30, 2020. One stage cluster sampling technique was used to select study participants. A pre-tested interviewer-based questionnaire was used to collect data. Data were entered in Epi info version 7 and were analyzed using statistical package for social sciences (SPSS) version 20 software. A bivariate and multivariable logistic regression model was fitted to identify factors associated with complementary feeding practice. The odds' ratio with a 95% confidence interval was computed to determine the level of significance. P-value is less than or equal to 0.05 considered significant.

Results: over all response rate was 100%. Among 416 mothers with children aged 6-23 months, 76.4% mothers started giving complementary feeding timely at recommended age of 6 month of child age. Advised about complementary feeding during ANC follow up [AOR=0.03; 95%CI: 0.003-0.356], child delivered in place at a health facility [AOR=0.07; 95%CI: 0.0-0.619], mothers take family planning [AOR=0.049; 95%CI: 0.011-0.23], give additional diet the first 6 months [AOR = 0.035; 95% CI: 0.009-0.137] and BF makes appearance [AOR = 0.064; 95% CI: 0.003-0.687] were found to be independent predictors of complementary feeding practice.

Conclusion: about 23.6% of mothers were not initiated complementary feeding practice in their children at the recommended age of 6 months. This would have negative implications on the health of infants and young children. There was a statistically significant association of initiation of complementary feeding practices with mothers´ advice about CF during ANC follow up, child delivered place at a health facility, take family planning, give additional diet the 1st 6 months, and mothers´ think BF makes an appearance. Health professionals should focus on advising and counseling mothers on appropriate complementary feeding during prenatal, delivery, postnatal, and immunization services.

Complementary feeding refers to when breast milk alone is no longer sufficient to meet the nutritional requirements of infants; therefore it means the feeding of solid, semi-solid, or soft foods in addition to breastfeeding. According to the World Health Organization, complementary feeding should be introduced timely at 6 months of age, sufficient meal frequency, and diversity of diet. The transition from exclusive breastfeeding to family foods covers the period from 6 - 23 months of age, even though breastfeeding may continue to two years of age and beyond [1]. Complementary feeding (CF) should be timely (start receiving from 6 months onward) and adequate (in amounts, frequency, consistency, and using a variety of foods). The foods should be prepared and given in a safe manner and be given in a way that is appropriate (foods are of appropriate texture for the age of the child) and applying responsive feeding following principles for psychosocial care [2,3]. From the sixth month onward, complementary foods should be of variety, and balanced mixtures of food items containing cereals, foods of animal and vegetable origin, and fat should be offered. Only a varied diet guarantees the supply of micronutrients enhances good eating habits and prevents the development of anorexia caused by monotonous foods. Grain products (whole grain) can serve as sources for carbohydrates, fibers, and micronutrients such as thiamin, niacin, riboflavin, and iron. Protein-rich foods, such as meat, poultry, fish, egg yolks, cheese, yogurt, and legumes, can be introduced to infants between 6 and 8 months of age [3-5]. Complementary foods usually are of two types, thus are commercially prepared infant foods bought from the market and homemade complementary foods, which are prepared at the household level by the caregivers following traditional methods [6,7]. Complementary feeding is important during the period of 6-23 months since it is also regarded as a “critical window” for a child´s health, growth, and development. A review reported that CF should be timely starting at 6 months, adequate (in amount and variety) [8]. An assessment of the CF practices among different subpopulations is significant for understanding the meal frequencies and diversity of diets of children at 6-23 months. CF practices are still poor in most developing countries and are even worsening in some of them. The achievement of universal coverage of optimal breastfeeding could prevent 13% of death occurring in under-five years´ children globally. While appropriate CF practice would result in an additional 6% reduction in under-five mortality [9].

Malnutrition has been responsible for 60 percent of the 10.9 million deaths annually among children under five, globally. Over two-thirds of these deaths, which are often associated with inappropriate CF practice and infectious disease, occur during the first year of life [1]. The majority of these deaths occur in sub-Saharan Africa, and the major contributors to their death are poor optimal BF and CF [10]. It is estimated that suboptimal CF in the first six months of life results in 1.4 million deaths and 10 percent of the disease burden in children younger than five years [11]. Globally, minimum meal frequency is at 52.2%, minimum dietary diversity is 29.4% and minimum acceptable diet is at 16% [12]. Uganda has got a national policy on infants and young child feeding, although considerable progress has been made over the last few decades towards the implementation of programs designed to promote EBF; CF practice has lagged behind over the same period. Exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) is at 65.7%, while CF is at 14% [13]. Progress in CF has been hampered mainly due to the lack of standard indicators to assess for CF previously, not until 2008 when core indicators were introduced [1]. Studies done in Nigeria prevalence of initiation of CF Were 54% [14], and studies conducted in Iran, Kenya prevalence of initiation of CF were, 83.6%, 85.4% respectively [15,16]. In Ethiopia, the rate of stunting, underweight and wasted among under-five children were 37%, 21%, and 7% respectively, and also it is one of the countries with the highest infant and child mortality rates in the world, infant mortality and under-five mortality rates are 43/1,000 and 55/1,000 live births respectively. Complementary feeding practices are critical public health measures to reduce and prevent morbidity and mortality in young children in order to achieve the sustainable development goal 4 [17,18]. About 50% of child death is related to malnutrition, which can be preventable through appropriate CF practice, including breastfeeding. Breast milk and CF could prevent 13% and 6% of under 5 child mortality, respectively [19].

Analysis of demographic and health survey data on infant and young child feeding practice in Ethiopia 2019 for infant and young child feeding (IYCF) compression showed that the practice of CF age 6-9 months was 71.2 [20]. In the Amhara region of Ethiopia, practice of CF and minimal dietary diversity is 34.6% and 2.1% respectively [21]. Studies done in a different area of Ethiopia Initiation of CF practice were in Hiwot Fana Specialized Hospital, Eastern Ethiopia 60.5% [22], in Benishangul Gumuz Region, Ethiopia 61.8% [23], in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia 83% [24], in Northern Ethiopia 15% [25], in Halaba Kulito town, Southern Ethiopia 57.8% [26], in Southern Ethiopia 97.6% [27], in Northern Ethiopia 62.8% [28], in Sodo town, Southern Ethiopia 71.2% [29], in rural Soro district of Southwest Ethiopia 34.3% [30]. An institution-based cross-sectional study in Gondar town among infant and young children showed that 89.5% of mothers followed the recommended way of infant feeding practice [31]. In another study Lasta District, about 43.5% of mothers were not feeding their children complementary food appropriately [32]. However, the implementation of the strategy has remained inconsistent, and health messages lacked focus on factors that influence maternal practice excluding infants from getting CF practice. This study tries to assess the practice of these mothers about the prevalence of CF in their infants. If this downside continues, the number of infant´s death will increase because of Malnutrition particularly at the infant stage of development. However, no studies were documented about the prevalence of complementary feeding of infants in the study area. To make some contribution to Meket Woreda and its surrounding Keble´s, an attempt has been made to investigate the prevalence of complementary feeding practice and its associated factors among mothers with children aged 6-23 months. Hence, this study is very important to assess the prevalence of initiation of complementary feeding practice and its associated factors among mothers with children aged 6-23 months in Meket District, North Wollo Ethiopia, 2020 (Figure 1).

Study area and period: the study was conducted in selected Keble of Meket Woreda Northwest, Ethiopia. Meket Woreda is the largest Woreda of the North Wollo zone. It is located about 205 km away from Bahir Dar, the regional capital city, and 709 km far from Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia. The total population is 243,549 people of which 119339 are males and 124210 females and there are 32977 under-five children, 12299 under two years´ children, and 10692 children aged 6-23 months in the Woreda There are 2 urban and 34 rural Keble in Meket Woreda. There are 1 primary hospital, 7 governmental health centers, and 36 health posts in the Woreda [33]. The study was conducted from June 2020 to December 2020.

Study design and participants' characteristics: community based multi central cross-sectional study design was conducted. All mother-child pairs from 6-23 months in Meket Woreda; who residing for more than six months were the source population. Sample mother-child pairs from 6-23 months in Meket Woreda who fulfill the inclusion criteria were the study participants in this study.

Sample size determination: the sample size was calculated using single population proportion formula by assuming p=prevalence of CF practice of mothers 56.5% taken from the study conducted in Lasta District [32], Z = 1.96 and D = precision (marginal error) = 5%, the sample size was calculated as follows;

Where n=sample size needed z = standard normal variable at 95% confidence level (1.96) p = the prevalence of CF in Lasta District (0.565) d = margin of error (0.05) Z α/2= value of standard normal distribution corresponding to significant level of alpha (α) 0.05 which is 1.96. Taking 10% [13] non-response rate, the final sample size was NRR=38 then 38+378=416.

Sampling procedure: there are 36 Kebeles in the Woreda and cluster sampling was used to take the appropriate sample. Initially, Meket Woreda was classified into 36 clusters based on the number of Kebeles. Then nine clusters were selected randomly by lottery method. The households were identified by health extension workers (a pre-survey was conducting before the actual day of data collection to determine which households have the target mother-child pairs). The data collection was started at one of the selected Kebele by lottery method and continues to the next Kebele. The first household was selected randomly, and the subsequent household was selected according to the principle of the next to the nearest household. Households in the clusters were visited until all proportion samples included. When two or more eligible mothers to child pairs were found, only one was included by the lottery method. For an eligible participant that was not found at home during data collection, the interviewers were revisiting the household three times at different time intervals and when interviewers failed to get the eligible participant, the household was registered as non-response.

Operational definition: breastfeeding: is a means of infants and young children feeding with milk from a woman´s breast. Initiation of complementary feeding at 6 months of age: started CF (start (initiate) additional foods to a child besides breast milk) at 6 months child [1,24,26]. Early introduction of CF: proportion of breastfed children 6-23 months of age who had been introduced to CF before 6 months of age [29]. Exclusive breastfeeding: refers to feeding infants only with breast-milk up to 6 months. Infant and young child feeding: is feeding a child until two years of age. Mother´s knowledge complementary feeding: mother's IYCF knowledge was determined using knowledge item questions, accordingly, respondents were asked about IYCF item questions Then, if the mothers correctly answer 50% or more of the above knowledge questions, she will be considered as having good knowledge, otherwise, below 50% will be a poor knowledge [23]. Complementary feeding: is the process of starting additional foods when breast milk alone is no longer sufficient to meet the nutritional requirements of infants [26].

Data collection tools and techniques

Data collection tools: data were collected using a pre-tested and structured interviewer-administered questionnaire, which was adapted from UNSF and other different articles [19,22,24,27-30,32,34-37,38], the questionnaire was prepared in the English version, and it translated to the local language (Amharic which was used to collect the data). The questionnaire has fifty-nine questions and four parts: socio-demographic and economic characteristics' assessment status, maternal obstetric and health care service related assessment, knowledge and pattern of complementary feeding 6-23 months factors, and measuring maternal attitudes towards complementary infant feeding related assessment.

Data collection techniques: a total of two diploma nurses as data collector and two B.Sc. nurses as a supervisor (who have an experience of data collection) were selected. After briefly presenting the study purpose and getting oral consent from each mother with an eligible infant, data collectors interviewed participants.

Data quality control: the quality of the data was assured by pre-testing the questionnaire on 5% of the sample (31 mothers with an eligible infant) in Flakit Keble prior to the start of the actual study to test the fitness of the questionnaire for the study settings. Training about the data collection tool as well as data collection procedures (ways of approaching the eligible mothers and how to obtain permission for an interview) was given to data collectors and supervisors for a total of one day prior to the data collection process. The objectives of the study were clearly explained to the data collectors as well as supervisors. The respondents were given a brief orientation before they are interviewed, and supervision was done on the spot by the supervisors. Throughout the course of the data collection, interviewers were supervised at each site, regular meetings were held between the data collectors, supervisor, and the principal investigator to discuss the problem arising in each interview, and detailed feedback was provided to the data collectors. In addition, the collected data was checked daily for its completeness, accuracy, and clarity by supervisors. The principal investigator was checked in every questionnaire before data entry. Data was kept in the form of a file in a private, and secured place.

Data processing and analysis: after checking the completeness of the data, it was entered into Epi data version 3.1.1, and then; it was exported to SPSS Version 20 for analysis. Descriptive analysis was due by computing proportions and summary statistics. The association between each independent variable and the outcome variable will assess by using binary logistic regression. All variables with P ≤ 0.2 in the bivariate analysis were included in the final model of multivariable analysis in order to control all possible confounders. Adjusted odds' ratio along with 95% CI will compute and P-value < 0.05 will consider declaring factors that have statistically significant association with International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) by using multivariable analysis in the binary logistic regression. The goodness of fit was tests by Hosmer-Lemeshow statistic test. Finally, the result is presented in the form of texts, tables and graph.

Ethical consideration: ethical clearance was obtained from the ethical review committee of Debre Tabor University, College of Health Sciences. Before the beginning of data collection, permission letter was obtained from Meket Woreda health bureau and from each Kebele administration. Then, the participants of the study were informing about the purpose of the study, the importance of their participation, and their right to withdraw at any time. Verbal informed consent was obtained prior to data collection. Mothers who do not practice ICF at 6 months during the data collection period were advised regarding infant feeding. All the information given by the respondents was used for research purposes only and confidentiality and privacy was maintained by omitting the name of the respondents during data collection procedure.

Socio-demographic characteristics of mothers: among 416 sampled mothers, 416 were successfully included in the study making the response rate of 100%. The median age of mothers was 29 years with inter quartile range (IQR) being 8. Three hundred and seventy three (89.7%) were orthodox by religion while others (8.9%) Muslim, (1.4%) Protestant and most of them (96.9%) belong to the Amhara ethnic group. Concerning the educational status of mothers, 123 (29.6%) respondents were unable to read and write the other 151 (36.3%) had attended formal school. The majority of mothers, 350 (84.1%), were married and 26 (62.5%) were house wives by occupation. More than a half, 244 (58.7%), of mothers earned an average monthly income was between in the range of 500-3000 Ethiopian Birr. Husbands of 192 (46.1%) mothers had attended formal education. The median age of children was 12 months with IQR being 8, sex of the children 219 (52.6%) male and 197 (47.4%) were female (Table 1).

Obstetrics and health service related variables: the majority of mothers, 305 (73.3%), had antenatal care follow-up during the last pregnancy. Of respondents 51 (12.3) had only the first antenatal care follow up and 32.2% (134/416) of mothers had at least four visits as recommended. About 270 (64.9%) of mothers give birth to their last child at a health institution. Approximately 248 (59.6%) had received postnatal care (PNC) at least once (Table 2).

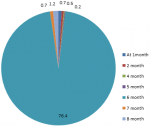

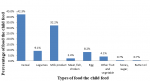

Complementary feeding knowledge and practices: in this study, it was found that the majority (82.9%) of mothers had ever practiced breastfeeding exclusively. Approximately 80% (333/416) of mothers had satisfactory knowledge and the rest 19.7% had poor knowledge about started complementary feeding. About 32.5% (135/416) of mothers had a supportive attitude while the rest 67.5% had no supportive attitude towards complementary feeding. Cereal and milk products were the most commonly taken food items of the children (42.3% and 32.2%) respectively. Legumes and nuts (9.1%), vitamin-A-rich foods (2.4%), other fruits and vegetables (4.1%), and egg (8.2%) generally the rates of different food groups offered were uniformly lower in the 6-23 months child age group. The 76.4% (95% CI: 318/416) of mothers introduced complementary feeding at 6 months age of the children as per recommended. Only 7 (1.7%) mothers introduced complementary feeding early before 6 months, 8 (1.9%) mothers initiated late after 6 months and 83 (20%) mothers did not start complementary feeding at all ( Table 3), (Figure 2, Figure 3).

Attitudes of mothers on complementary infant feeding: concerning the attitudes of mothers towards complementary infant feeding most respondents (30.3%) were not agreed with the item that states about complementary foods make the infants fat, and also (22.6%) shows the strong agreement on the item it makes their infants fat. The majority of the respondents (39.7%) responded that even though they have sufficient money to buy complementary foods they prefer to suffer themselves on breastfeeding their infants but 15.3% of the participants agree to buy complementary foods than suffering themselves by breastfeeding. This implies that for these mothers breastfeeding is not based on interest but only the shortage of money to buy complementary foods makes them breastfeed. Regarding the early initiation of complementary foods 38.4% of the respondents agreed that just after birth they introduced their infants to complementary foods. The other number (17.8%) of the participants replied that even if their breast does not have sufficient milk they never introduced their newborn infants to complementary foods. On the process of providing complementary foods, the vast majority of the respondents (35.8%) reported that they like the item stated since others help them in providing complementary foods because others can help them in feeding it. Others (15.6%) said that were not agreed with this idea. Concerning the physical appearance and complementary foods of the respondents, (14.6%) said that since breastfeeding makes our appearance thin we prefer to give complementary foods. Others (27.2%) replied that they did not give complementary foods even breastfeeding make their appearance thin. This indicates that mothers in this particular culture have a strong desire to breastfeed than complementary feeding practice. Concerning the issue of complementary foods with health effects, most participants (50.7%) revealed that complementary foods make their infants healthy and strong. But a few (11.1%) of the respondents reported that complementary foods cannot make their infants healthy and strong. Lastly, 15.6% of the participants agreed that instead of breast milk after six months, complementary foods are preferable or should be given more weight (Table 4).

Prevalence of initiation of complementary feeding practice: in this study among 416 mothers with children aged 6-23 months, 76.4% of mothers started giving complementary feeding timely at the recommended age of 6 months of child age factors found associated with initiation of complementary feeding practice. After applying bivariate and multiple logistic regressions, five variables were found to be significantly associated with initiation of complementary feeding practice. These were mothers had family planning [AOR= 0.049; 95%CI: 0.011-0.23], mothers who had Antenatal care follow up [AOR=0.03; 95%CI: 0.003-0.356], Child delivered place at a health facility [AOR=0.07; 95%CI: 0.0-0.619], give additional diet the first 6 months [AOR = 0.035; 95% CI: 0.009-0.137] and were BF makes appearance [AOR = 0.064; 95% CI: 0.003-0.687] more likely to initiate complementary feeding to their children (Table 5).

In this study among 416 mothers with children aged 6-23 months, 76.4% of mothers started giving complementary feeding timely mothers having children 6-23 months of age, In Meket Woreda, North Wollo Ethiopia 2020. This study showed that 76.4% of mothers in Meket Woreda, North Wollo Ethiopia mothers having children 6-23 months of age. This finding was in line with a study conducted analysis of demographic and health survey data on infant and young child feeding practice in Ethiopia 2019 for IYCF compression showed that practice of CF Age 6-9 months were 71.2% [20]. In Ethiopia practice of CF in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia 83% [24], in Sodo town, Southern Ethiopia 71.2% [29]. The similarity of this study could be the study design and socio-cultural resemblance among the society on infant feeding practices. Studies conducted in Iran, Kenya prevalence of initiation of CF was, 83.6%, 85.4% respectively [15,16]. The similarity of this study could be the study design on infant feeding practices.

However, the result of this study was much lower than the study done in Southern Ethiopia at 97.6% [29]. An institution-based cross-sectional study in Gondar town among infant and young children showed that 89.5% of mothers followed the recommended way of infant feeding practice [31]. The probable reason for the above difference in rates could be variation in information dissemination on child feeding practice. This result was higher as compared with other similar studies such as on research done In Amhara region of Ethiopia practice of CF and minimal dietary diversity is 34.6% and 2.1% respectively [21]. Studies done in a different area of Ethiopia Initiation of CF practice were in Hiwot Fana Specialized Hospital, Eastern Ethiopia 60.5% [22], in Benishangul Gumuz Region, Ethiopia 61.8% [23], in Northern Ethiopia 15% [25], in Halaba Kulito town, Southern Ethiopia 57.8% [26], in Northern Ethiopia 62.8% [28], in rural Soro district of Southwest Ethiopia 34.3% [30]. In another study Lasta District, About 43.5% of mothers were not feeding their children complementary food appropriately [32]. According to the World Health Organization, CF should be introduced timely at 6 months of age, sufficient meal frequency, and diversity of diet. At 6 months breast milk provides 60 percent of the total dietary energy requirement and the 40 percent should be derived from complementary foods [1]. The magnitude of CF practice is unacceptably low in the studies conducted in different countries of the world like 32% in India [39], 37% in Zambia [40], and 15.7% in Ghana [41]. These studies also indicated low minimum dietary diversity. Studies done in Nigeria Prevalence of Initiation of CF Were 54% [2]. The reason why these discrepancies happened may be due to the presence of variations in geographical location, socio-cultural practices, policies, and economic status.

In multiple logistic regressions, significantly associated with initiation of complementary feeding practice. These were mothers had family planning [AOR= 0.049; 95%CI: 0.011-0.23], mothers who had Antenatal care follow up [AOR=0.03; 95%CI: 0.003-0.356], Child delivered place at a health facility [AOR=0.07; 95%CI: 0.0-0.619], give additional diet the 1st 6 months [AOR = 0.035; 95% CI: 0.009-0.137] and were BF makes appearance [AOR = 0.064; 95% CI: 0.003-0.687] more likely to initiate complementary feeding to their children. This finding was supported by the study done in Lalibela District, Northeast Ethiopia, antenatal care, and institutional delivery was reported to be significantly associated with appropriate complementary feeding [34]. A high frequency of antenatal visits (4+) was associated with appropriate complementary foods as compared to mothers who did not attend antenatal care, these findings suggest that mothers who attend antenatal care have better access to health services such as nutrition counseling and respond to health information messages on CF. Similarly, this might be due to the fact that home-delivered mothers would not have sufficient information about recommended child feeding practices, and they are more influenced by communities´ inappropriate child feeding practices (IACFP) and also study conducted on the risk factors of poor CFP found delayed maternal postnatal checkup as a significant factor that increased the odds of not meeting the criteria for ACF [42]. According to the study done in Benshangul, Ethiopia, mother's postnatal checkup, showed significant associated with CF [AOR (95% CI) = 1.68 (1.15,2.45)][23]. Study conducted in Adiss Abeba Ethiopia, mother´s attend ANC, made a plan for reaching the facility during labor, place of delivery at health facility, Postnatal care attendance [AOR (95% CI)= 0.89 (0.24], [AOR (95% CI)= 0.69 (0.37,1.26)], [AOR (95% CI)= 0.32 (0.12,0.82], [AOR (95% CI)= 0.75 (0.46,1.23)], showed significant associated with CF respectively [24].

Study conducted in Halaba Kulito town, Southern Ethiopia, place of delivery, at Health Center, Hospital [AOR (95% CI)= 2.36 (0.67, 8.31)], [AOR (95% CI)= 2.79(0.66, 11.86)], showed significant associated with CF respectively [38]. Study done in Arsi Negele, Southern Ethiopia, place of delivery, health facility, attended ANC, attended PNC, attended HDAs (1-5) [AOR (95% CI) = 1.37 (0.74-2.55)], [AOR (95% CI) =1.65 (0.11-24.85)], [AOR (95% CI) =1.86 (0.79-4.36)], [AOR (95% CI) =1.61 (0.70-3.68)], showed significant associated with CF respectively [38]. Study conducted in Sodo town, Southern Ethiopia, mothers follow ANC, mothers follow PNC, place of delivery, health facilities [AOR (95% CI) =3.30(1.21-8.99)], [AOR (95% CI) =0.92(0.62-1.40)], [AOR (95% CI) =3.15(1.61-6.17)], showed significant associated with CF Respectively [29]. Study conducted in Mekelle Town, Northern Ethiopia, source of information, mothers follow ANC, mothers not follow PNC, place of delivery, health facility, [AOR (95% CI) =2.845 (1.240, 6.528)], [AOR (95% CI)=0.860 (0.492,1.505)] showed significant associated with CF respectively [28]. Study conducted in Tahtay Maichew district, northern Ethiopia, mother follow ANC, mothers not follow PNC, [AOR (95% CI) =1.58 (0.60-4.21)], [AOR (95% CI) =1.15 (0.94-1.41)] showed significant associated with CF respectively [35]. Study conducted in Soro district, South Ethiopia, institutional delivery, [AOR (95% CI) =0.79(0.21], showed significant associated with CF [30].

Almost two-thirds of mothers initiated complementary feeding at the sixth month of child age, that is a relatively higher prevalence than in other countries. In order to reduce the high infant mortality, this level has to be increased, since 23.6% of the mothers are still not starting complementary feeding at six months. This would have negative implications on the health of infants and young children. There was a statistically significant association of initiation of complementary feeding practices with mothers´ advised about CF during ANC follow up, child delivered place at a health facility, take family planning, give additional diet the 1st 6 months, and mothers´ think BF makes an appearance, were factors that can increase appropriate complementary feeding practice.

Limitations of the study: due to the retrospective nature of the study, there might be a recall bias.

Recommendation

For Woreda health bureau and zone health office: nutrition education should be delivered in a good manner by giving special emphasis on child feeding practices through health extension programs and nutrition advocacy through the use of mass media. Health extension workers should be trained to provide health services at the community level to reduce the prevalence of communicable diseases and to improve the coverage of the timely introduction of complementary feeding. It is better to assign nutrition professionals at the health institution and Woreda health office level. It is better to strengthen the inter-sectorial involvement of organizations working on nutrition promotion to realize nutrition interventions. Health professionals should focus on advising and counseling mothers on appropriate and timely initiation of complementary feeding during prenatal, delivery, postnatal, and immunization services. Developing motivational factors for mothers who practice complementary feeding appropriately could be promotion (advertising) of complementary feeding.

To the researchers: further research is needed to identify related factors of the timely introduction of complementary feeding, especially qualitative aspects, i.e. attitude and beliefs of the community related to timely introduction of complementary feeding.

What is known about this topic

- Complementary feeding refers to when breast milk alone is no longer sufficient to meet the nutritional requirements of infants; therefore it means the feeding of solid, semi-solid, or soft foods in addition to breastfeeding;

- According to the World Health Organization, complementary feeding should be introduced timely at 6 months of age, sufficient meal frequency, and diversity of diet. The transition from exclusive breastfeeding to family foods covers the period from 6 to 23 months of age, even though breastfeeding may continue to two years of age and beyond;

- Complementary feeding (CF) should be timely (start receiving from 6 months onward) and adequate (in amounts, frequency, consistency, and using a variety of foods). The foods should be prepared and given in a safe manner and be given in a way that is appropriate (foods are of appropriate texture for the age of the child) and applying responsive feeding following principles for psychosocial care.

What this study adds

- Over all response rate was 100%;

- Among 416 mothers with children aged 6-23 months, 76.4% mothers started giving complementary feeding timely at recommended age of 6 month of child age;

- Advised about CF during ANC follow up [AOR=0.03; 95%CI: 0.003-0.356], Child delivered in place at a health facility [AOR=0.07; 95%CI: 0.0-0.619], mothers take family planning [AOR=0.049; 95%CI: 0.011-0.23], give additional diet the first 6 months [AOR=0.035; 95% CI: 0.009-0.137] and BF makes appearance [AOR=0.064; 95% CI: 0.003-0.687] were found to be independent predictors of complementary feeding practice.

The authors declare no competing interests.

DGF, the corresponding author, worked on designing the study, training and supervising the data collectors, interpreting the result, and preparing the manuscript. The co-authors namely AYT, ESC, AKW, SFT, GMW, ATA, TD, EMA, MMA, FAG, SAA played their role in analyzing and interpreting the result. Moreover, the co-authors wrote the manuscript. All the authors have read and agreed to the final manuscript.

The author acknowledged data collectors, and supervisors. The author is also deeply acknowledging Debre Tabor University. Last but not least, the respondents deserve sincere thanks for their kind responses.

Table 1: socio-demographic related variables of mothers who had children aged 6-23 months (n = 416) in Meket Woreda, Amhara, North east Ethiopia, June 2020 to December 2020

Table 2: obstetric, and health-related variables of mothers who had children aged 6-23 months (n = 416) in Meket Woreda, Amhara, North central Ethiopia, June 2020 to December 2020

Table 3: complementary feeding knowledge and practice of mothers who had children aged 6-23 months (n = 416) in Meket Woreda, Amhara, North central Ethiopia, June 2020 to December 2020

Table 4: the attitude of mothers towards complementary infant feeding who had children aged 6-23 months (n = 416) in Meket Woreda, Amhara, North central Ethiopia, June 2020 to December 2020

Table 5: multivariable logistic regression analysis of factors associated with the initiation of complementary feeding at 6 months of age among mothers of children aged 6-24 months (n = 416) in Meket Woreda, Amhara, North central Ethiopia, June 2020 to December 2020

Figure 1: conceptual framework for the study on Initiation of complementary feeding practice and associated factors among mothers having children 6-23 months of age, in Meket Woreda, North Wollo Ethiopia, 2020

Figure 2: time at which complementary feeding was initiated by mothers who had children aged 6-23 months (n = 416) in Meket Woreda, Amhara, North central Ethiopia, June 2020 to December 2020

Figure 3: types of food initiated as complimentary food of mothers who had children aged 6-23 months (n = 416) in Meket Woreda, Amhara, North central Ethiopia, and June 2020 to December 2020

- World Health Organization. Indicators for assessing infant and young child feeding practices. Part 1: definitions 2008, Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. 2016.

- World Health Organization. Global strategy for infant and young child feeding. World Health Organization. 2003. Google Scholar

- Monte C, Giugliani E. Recommendations for the complementary feeding of the breastfed child. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2004;80(Suppl 5):S131-41. PubMed | Google Scholar

- WHO. Infant and young child feeding: model chapter for textbooks for medical students and allied health professionals. WHO. 2009. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Food, Organization A. The state of food insecurity in the world: how does international price volatility affect domestic economies and food insecurity?. Publishing Policy and Support Branch: FAO Rome. 2011.

- Ng CS, Dibley MJ, Agho KE. Complementary feeding indicators and determinants of poor feeding practices in Indonesia: a secondary analysis of 2007 demographic and health survey data. Public Health Nutrition. 2012;15(5):827-39. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Hotz C, Gibson RS. Traditional food-processing and preparation practices to enhance the bioavailability of micronutrients in plant-based diets. The Journal of Nutrition. 2007;137(4):1097-100. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Abeshu MA, Lelisa A, Geleta B. Complementary feeding: a review of recommendations, feeding practices, and adequacy of homemade complementary food preparations in developing countries-lessons from Ethiopia. Frontiers in Nutrition. 2016;3:41. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Kimani-Murage EW, Wekesah F, Wanjohi M, Kyobutungi C, Ezeh AC, Musoke RN et al. Factors affecting actualization of the WHO breastfeeding recommendations in urban poor settings in Kenya. Maternal & Child Nutrition. 2015;11(3):314-32. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Arts M, Taqi I, Bégin F. Improving the early initiation of breastfeeding: the WHO-UNICEF breastfeeding advocacy initiative. Breastfeeding Medicine. 2017;12(6):326-7. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Henry ME. Formula use in a breastfeeding culture: changing perceptions and patterns of young infant feeding in Vietnam. Johns Hopkins University. 2015. Google Scholar

- White JM, Bégin F, Kumapley R, Murray C, Krasevec J. Complementary feeding practices: current global and regional estimates. Maternal & Child Nutrition. 2017 Oct;13 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):e12505. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Mokori A, Schonfeldt H, Hendriks SL. Child factors associated with complementary feeding practices in Uganda. South African Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2017;30(1):7-14. Google Scholar

- Okafoagu NC, Oche OM, Raji MO, Onankpa B, Raji I. Factors influencing complementary and weaning practices among women in rural communities of Sokoto State, Nigeria. Pan Afr Med J. 2017 Nov 22;28:254 PubMed | Google Scholar

- Jacob Kipruto Korir. Determinants of complementary feeding practices and nutritional status of children 6-23 months old In Korogocho Slum, Nairobi County, Kenya. Kenyatta University. 2013. Google Scholar

- Fatemeh Abdollahi, Jamshid Yazdani Chareti Rohani S. Study of complementary feeding practices and some related factors among mothers attending primary health centers in Sari. Iran J Health Sci. 2014;2(3):43-48. Google Scholar

- Ethiopia Mini Demographic and Health Survey (2019 EMDHS). Was neonatal mortality levels; child nutrition, and other health issues. EMDHS. 2019:20. PubMed | Google Scholar

- EDHS. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2011. Accessed February 20, 2021.

- UNICEF programming guide: infant and young child feeding.. Accessed February 20 22021.

- Ethiopia. Ethiopia Mini Demographic and Health Survey 2019. Accessed February 20, 2021.

- Disha A, Tharaney M, Abebe Y, Alayon S, Winnard K. Factors associated with infant and young child feeding practices in Amhara region and nationally in Ethiopia: analysis of the 2005 and 2011 demographic and health surveys. Washington, DC: Alive and Thrive. 2015.

- Semahegn A, Tesfaye G, Bogale A. Complementary feeding practice of mothers and associated factors in Hiwot Fana Specialized Hospital, Eastern Ethiopia. Pan Afr Med J. 2014 Jun 17;18:143. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Ayana D, Tariku A, Feleke A, Woldie H. Complementary feeding practices among children in Benishangul Gumuz Region, Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. 2017 Jul 27;10(1):335. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Mohammed S, Getinet T, Solomon S, Jones AD. Prevalence of initiation of complementary feeding at 6 months of age and associated factors among mothers of children aged 6 to 24 months in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Nutr. 2018 Dec 29;4:54. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Belete Y, Awraris W, Muleta M. Appropriate complementary feeding practice was relatively low and associated with mother´s education, family income, and mother´s age: a community based cross-sectional study in Northern Ethiopia. Journal of Nutritional Health & Food Engineering, 2017.

- Desalegn Tsegaw Hibstu, Dawit Jember Tesfaye, Teshome Abuka Abebo, Fanuel Belayneh Bekele. Complementary feeding timing and its predictors among mothers´ of children aged (6-23) months old in Halaba Kulito town, Southern Ethiopia. Curr Pediatr Res. 2018;22(1):61-68. Google Scholar

- Kassa T, Meshesha B, Haji Y, Ebrahim J. Appropriate complementary feeding practices and associated factors among mothers of children age 6-23 months in Southern Ethiopia, 2015. BMC Pediatrics. 2016;16(1):131. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Ashenafi Shumey, Meaza Demissie, Yemane Berhane. Timely initiation of complementary feeding and associated factors among children aged 6 to 12 months in Northern Ethiopia: an institution-based cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:1050. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Chane T, Bitew S, Mekonnen T, Fekadu W. Initiation of complementary feeding and associated factors among children of age 6-23 months in Sodo town, Southern Ethiopia, Cross-sectional study Pediatric Reports. Pediatr Rep. 2018 Jan 3;9(4):7240. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Yohannes B, Ejamo E, Thangavel T, Yohannis M. Timely initiation of complementary feeding to children aged 6-23 months in rural Soro district of Southwest Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pediatr. 2018 Jan 31;18(1):17. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Muluye D, Woldeyohannes D, Gizachew M, Tiruneh M. Infant feeding practice and associated factors of HIV positive mothers attending prevention of mother to child transmission and antiretroviral therapy clinics in Gondar Town health institutions, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:240. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Molla M, Ejigu T, Nega G. Complementary feeding practice and associated factors among mothers having children 6-23 months of age, Lasta District, Amhara region, Northeast Ethiopia. Advances in Public Health. 2017;2017. Google Scholar

- Tatiana O Vieira, Graciete O Vieira, Elsa Regina J Giugliani, Carlos MC Mendes, Camilla C Martins, Luciana R Silva. Determinants of breastfeeding initiation within the first hour of life in a Brazilian population: a cross-sectional study. BMC. 2010. Google Scholar

- Sisay W, Edris M, Tariku A. Determinants of timely initiation of complementary feeding among mothers with children aged 6-23 months in Lalibela District, Northeast Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):884. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Agumasie Semahegn, Gezahegn Tesfaye, Alemayehu Bogale. Complementary feeding practice of mothers and associated factors in Hiwot Fana Specialized Hospital, Eastern Ethiopia. Pan Afr Med J. 2014 Jun 17;18:143. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Reda EB, Teferra AS, Gebregziabher MG. Time to initiate complementary feeding and associated factors among mothers with children aged 6-24 months in Tahtay Maichew district, Northern, Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. 2019 Jan 14;12(1):17. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Tigist Kassa, Berhan Meshesha, Yusuf Haji, Jemal Ebrahim. Appropriate complementary feeding practices and associated factors among mothers of children age 6-23 months in Southern Ethiopia. BMC Pediatrics. BMC Pediatr. 2016 Aug 19;16:131. PubMed | Google Scholar

- UNICEF. Infant and young child feeding, nutrition section program. New York: UNICEF. 2012.

- Rao S, Swathi P, Unnikrishnan B, Hegde A. Study of complementary feeding practices among mothers of children aged six months to two years-A studies from coastal south India. The Australasian Medical Journal. 2011;4(5):252-7. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Katepa-Bwalya M, Mukonka V, Kankasa C, Masaninga F, Babaniyi O, Siziya S. Infants, and young children feeding practices and nutritional status in two districts of Zambia. International Breastfeeding Journal. 2015 Feb 18;10:5. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Saaka M, Wemakor A, Abizari AR, Aryee P. How well do WHO complementary feeding indicators relate to the nutritional status of children aged 6-23 months in rural Northern Ghana. BMC Public Health. 2015 Nov 23;15:1157. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Manikam L, Prasad A, Dharmaratnam A, Moen C, Robinson A, Light A et al. Systematic review of infant and young child complementary feeding practices in South Asian families: the India perspective. Public health nutrition. 2018;21(4):637-54. PubMed | Google Scholar