Antibiotic prescribing habits among primary healthcare workers in Northern Nigeria: a concern for patient safety in the era of global antimicrobial resistance

Mohammed Mohammed Manga, Yahaya Mohammed, Sherifat Suleiman, Adeola Fowotade, Zainab Yunusa-Kaltungo, Mu’awiya Usman, Ahmed Aliyu Abulfathi, Muhammad Ibrahim Saddiq

Corresponding author: Mohammed Mohammed Manga, Department of Medical Microbiology and Immunology, Gombe State University and Federal Teaching Hospital Gombe, Gombe State, Nigeria

Received: 19 Jul 2021 - Accepted: 24 Aug 2021 - Published: 26 Aug 2021

Domain: Laboratory medicine,Infectious disease,Public health

Keywords: Antibiotic prescribing, antimicrobial resistance, patient safety, primary healthcare workers, Nigeria

©Mohammed Mohammed Manga et al. PAMJ-One Health (ISSN: 2707-2800). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article: Mohammed Mohammed Manga et al. Antibiotic prescribing habits among primary healthcare workers in Northern Nigeria: a concern for patient safety in the era of global antimicrobial resistance. PAMJ-One Health. 2021;5:19. [doi: 10.11604/pamj-oh.2021.5.19.30847]

Available online at: https://www.one-health.panafrican-med-journal.com/content/article/5/19/full

Research

Antibiotic prescribing habits among primary healthcare workers in Northern Nigeria: a concern for patient safety in the era of global antimicrobial resistance

Antibiotic prescribing habits among primary healthcare workers in Northern Nigeria: a concern for patient safety in the era of global antimicrobial resistance

![]() Mohammed Mohammed Manga1,&,

Mohammed Mohammed Manga1,&, ![]() Yahaya Mohammed2, Sherifat Suleiman3, Adeola Fowotade4, Zainab Yunusa-Kaltungo5, Mu’awiya Usman6, Ahmed Aliyu Abulfathi7,8,

Yahaya Mohammed2, Sherifat Suleiman3, Adeola Fowotade4, Zainab Yunusa-Kaltungo5, Mu’awiya Usman6, Ahmed Aliyu Abulfathi7,8, ![]() Muhammad Ibrahim Saddiq9

Muhammad Ibrahim Saddiq9

&Corresponding author

Introduction: antibiotic overprescribing is associated with antibiotic resistance worldwide but worst in developing nations. Minimal information exists on the antibiotic prescribing habits of essentially all cadres of healthcare workers in Nigeria, but particularly primary healthcare (PHC) workers. Our aim was to explore antibiotic prescribing habits of Nigerian primary healthcare workers in the context of increasing antibiotic resistance which has a direct effect on healthcare associated infections (HCAIs) and patient safety worldwide.

Methods: a questionnaire-based cross-sectional study was conducted among 442 primary healthcare workers across three Northern Nigerian states of Gombe, Sokoto and Kwara. Data obtained was analysed using SPSS version 20.

Results: antibiotic prescription rate was 98.2%. The most commonly prescribed antibiotics were amoxicillin (71.7%) and ampicillin/cloxacillin (70.1%) while the least was meropenem (4.1%). Major indicators of antibiotics abuse include unconfirmed typhoid fever (96.1%), non-specific vaginal discharge (95.4%), fresh trauma wound (91.3%), non-specific diarrhoea (87.1%) and common cold (85.9%). Additionally, about one-third of the respondents also routinely prescribe antibiotics to healthy birds (31.5%) and animals (18.3%). Identified reasons attributed to antibiotic overprescribing from the participants´ perspectives include lack of awareness (87.0%), lack of penalty (79.4%), desire to help patients (76.5%), pressure from sales representatives (61.0%) and patients´ pressure (58.3%). Overall, majority (85.8%) of respondents agrees that overprescribing is a cause of antimicrobial resistance.

Conclusion: overprescribing of antibiotics is common among PHC workers and could contribute significantly to the rising scourge of antimicrobial resistance and poses a threat to patient safety and associated increased burden of HCAIs.

Antibiotic overprescribing is associated with antibiotic resistance worldwide. Healthcare Associated Infections (HCAIs) are commonly due to multidrug resistant (MDR) pathogens, constituting a major threat to global patient safety. Disparities in prescribing habits exist both geographically and among different categories of healthcare workers due to different factors and determinants. Developing countries such as Nigeria could potentially harbour one of the highest burdens of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) due to indiscriminate and inappropriate prescribing with absent/weak regulations/guidelines. Primary healthcare personnel especially the community health extension workers (CHEWs) constitute the largest proportion of first-line healthcare providers in Nigeria. The prescription and consumption of antibiotics are poorly regulated at all healthcare levels in Nigeria. antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is associated with poor outcome among patients and constitutes a significant global public health burden, which is worst in developing countries where antimicrobial prescriptions are poorly or never regulated at all levels [1,2]. The burden of AMR is rising and without proper intervention, about 10 million lives may be lost annually by the year 2050 [2]. Several reasons have been attributed to the development of AMR besides the intrinsic traits of some microorganisms. Antibiotic resistance (ABR) has to do with failure of antibiotics to treat bacterial infections and is a subset of AMR which encompasses resistance to all antimicrobial agents including antifungal, antiviral and antiparasitic agents. Among the modifiable causes of antibiotic resistance is misuse and abuse of the drugs through unnecessary prescribing at all levels of healthcare delivery [2, 3]. The overall consumption of antibiotics in any community is a major determinant of development of AMR by most pathogens [4]. Antibiotic prescribing at community levels is generally under-reported worldwide compared to hospital based prescriptions [4]. Only a few community-based surveillance reports on antibiotic use and prescribing habits have highlighted the importance and potential role of such approach in providing valuable information necessary for the fight against AMR [4, 5]. At the community level, up to 75% of antibiotic used in both humans and animals are of unproven clinical relevance [6]. Studies to determine the appropriateness or otherwise of antibiotic prescribing have continued to explore all approaches to highlight the huge burden and challenges embedded in this all-time global threat to patient safety and to proffer possible solutions.

Regulating the sales, prescription, and consumption of antibiotics is the primary approach in conserving antibiotics through stewardship programmes [1,2,7]. This has substantially succeeded in many developed nations, mainly due to stronger health systems and regulations [7]. Although some efforts are being made in few hospitals, albeit with minimal success in developing nations, the vast majority of prescribers are within the communities and mainly among the primary healthcare workers. The PHC workers are largely ignored in most efforts at combating AMR in Nigeria. In northern Nigeria, most patent medicine stores, and primary healthcare services are handled by community health extension workers (CHEWs) who also form the majority of first-line antibiotic prescribers. The CHEWs receive only a minimal training on antimicrobial use and prescribing and allowed to manage few commonly encountered clinical conditions based on the National Standing Orders for Community Health Officers/Community Health Extension Workers [8]. Although there exist a relatively old national drug policy, Nigeria has virtually no functional and/or well circulated national antibiotic policy which is equally absent or non-functional in most hospitals [9]. Regulations and guidelines on the sales, prescription, and consumption of antibiotics are either weak or non-existent in most developing nations. The pharmacists council of Nigeria (PCN) have provided the guidelines for the issuance of the patent and proprietary medicines vendor´s licence (PPPMVL) and the PCN´s Approved Patent Medicines List with minimal adherence by the relevant healthcare personnel including the CHEWs [10-12].

In Nigeria, there is near absence of prescription monitoring and prescription only medicines (POM) such as antimicrobials are easily accessed over-the-counter (OTC) in pharmacies and by patent proprietary medicines vendors (PPMVs) [13]. Virtually all healthcare workers (e.g. doctors, nurses, pharmacists, medical laboratory scientists, CHEWs) and many members of the general public do prescribe or purchase all classes of antibiotics due to relative accessibility/availability and poor monitoring. Antibiotic prescribing to healthy food animals for enhanced growth and other reasons is also a growing challenge to antibiotic stewardship in Nigeria [14]. Wrong diagnosis on the basis of unreliable clinical evidence or unconfirmed diagnosis of some clinical conditions like typhoid fever and vaginal discharge have led to misuse and abuse of antibiotics with potential consequences of ABR especially in developing nations where laboratory support is weak, absent or grossly underutilized [15,16]. Poor antibiotic prescribing habits have also been associated with other misdiagnosed clinical conditions such cough/common cold and diarrhoea (which could be of viral aetiology) leading to the development of ABR [17]. The aim of our study was to determine the antibiotic prescribing habits of Nigerian primary healthcare workers (CHEWs) in the context of growing antibiotic resistance as a threat to patient safety globally. Findings from this study could subsequently trigger many research and intervention works with resultant improvement in antibiotic prescribing habits/practices at the PHC level for better patient safety.

This was a descriptive cross-sectional study in which self-administered paper-based questionnaires were distributed among 442 primary healthcare workers across three Northern Nigerian states of Gombe, Sokoto and Kwara (representing the north-east, north-west and north-central geopolitical regions of the country respectively). The populations of the three states based on the 2006 national population census are Gombe (2,365,040), Sokoto (3,702,676) and Kwara (2,365,353) [18]. Sample size was determined using the Cochran´s formula [19] for single population proportion. Prevalence was assumed at 50% while 80% power and 95% confidence intervals were considered, and a minimum sample size of 384 was obtained. Six hundred questionnaires were administered out of which 422 were retrieved. A convenience sampling method was used to administer questionnaires to all participants who verbally consented to take part in the study. Recruitments and data collection were conducted between January and June 2018 across the three selected states in northern Nigeria. Hard copies of the questionnaires which were jointly self-developed and approved by the authors were concurrently administered independently to all consenting and consecutive primary healthcare workers across the three states without any interference or inducements. The questionnaire was validated using a pilot survey involving 20% of the participants prior to subsequent administration, with satisfactory results. primary healthcare (PHC) workers who are not CHEWs (e.g. doctors, nurses and pharmacists) were excluded from the study. Questionnaires were retrieved by the same research assistants who administered them. Some relevant survey questions are as highlighted in Table 1 below. Data obtained was analysed using SPSS version 20 to obtain frequencies, proportions and percentages as presented in tables and charts below. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the research and ethics committee of the Federal Teaching Hospital Gombe (FTHG); NHREC/25/10/2013 and permission received from relevant state primary healthcare development agencies. Privacy and confidentiality of the information provided by participants was maintained all through the study.

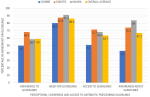

We recruited 442 participants aged 20 to 58 years with a mean age of 37 years. About two-third; 60.9% (269/442) of the participants were males. None of the participants was a medical doctor, nurse practitioner or pharmacist. All the respondents are CHEWS working in PHCs and majority 310 (72.4%) hold only the certificate or diploma qualifications while the remaining have additional qualifications in other health-related disciplines. Most (71.2%) of the respondents have been in practice for a period between 1 to 15 years, and almost all (98.2%) prescribe antibiotics. About 18.3% of the respondents prescribe antibiotics to healthy animals. Majority (85.8%) of the participants are aware that wrong antibiotic prescribing could lead to AMR and up to 76.1% knows about the existence MDR pathogens. The patterns of prescription of selected antibiotics and possible reasons for antibiotic misuse among the prescribers were as highlighted in Table 2 and Table 3, respectively. Figure 1 and Figure 2 summarize the level of awareness, access and adherence to available guidelines to prescribing and some possible reasons for lack of adherence to prescribing guidelines among the respondents.

This study confirms that almost all CHEWs in northern Nigeria prescribe antibiotics while majority (86.4%) agree on the need for regulations/guidelines, while about 2/3 have access and/or adhere to the “standing orders” and other documents guiding practice and antibiotic prescribing among CHEWS in Nigeria. Over use of antibiotics and suboptimal adherence to guidelines is not an uncommon feature in both developing and advanced settings [20,21]. As reported in some studies, our findings identified perceived reasons for not obeying the guidelines to include lack of awareness, absence or non-implementation of penalties, pressure from patients/sales representatives and the urgent/intense desire to assist patients [22]. In most developing nations such as Nigeria, factors such as the influence of pharmaceutical representatives and non-existent or weak policies/guidelines have all been identified as contributory to antibiotic overprescribing with resultant rise in AMR [4,23]. Patients´ pressure for prescribing even against the objective judgement of the prescribers as identified in more than half of our respondents (57.4%) is a well-known driver of irrational antibiotic prescribing [24,25]. Other reasons identified to contribute to inappropriate antibiotic prescribing include diagnostic uncertainty, poor/inadequate knowledge base, overstock/near expiry drugs, and financial considerations [25].

Although there are few hospitals in Nigeria that are making efforts at establishing antibiotic stewardship programmes, prescribers at the primary healthcare settings are virtually not regulated/monitored and have been observed to prescribe almost all classes of antibiotics without any restriction just as obtained in other low and middle income countries (LMICs) [4,26]. This poses a major threat to patient safety as it could potentially be a major driver to the development of antibiotic resistance in Nigeria. The national standing orders for community health officers (CHOs)/community health extension workers (CHEWs) provides uniform guidelines and allows for the use of few selected/essential antibiotics (e.g. cotrimoxazole, amoxycillin, ampiclox e.t.c.) for certain medical conditions to be treated at the primary healthcare level.[8] Adherence to this guideline is suboptimal in virtually all states of the federation. Frequency of antibiotic prescription especially among primary healthcare workers with 98.2% as observed in this study further confirms the high level of antibiotic prescribing in Nigeria compared to other countries including reports among doctors in tertiary hospitals [23,27,28]

Inappropriate antibiotic prescribing for different clinical conditions is a well-known habit with acute respiratory tract and related infections constituting the majority in both developed and developing countries [3,6,24,28-30]. In this study, unconfirmed typhoid fever, non-specific vaginal discharge, fresh trauma wound, non-specific diarrhoea and common cold attracted the most among the inappropriately prescribed antibiotics. Many of these have not been reported in most studies, as they are not conventional indicators for antibiotic usage. However, our study identifies these wrong indicators, which are mainly symptoms of not necessarily infections resulting to inappropriate antibiotic prescribing. Clinical diagnosis of typhoid, cough and diarrhoea have been associated with risk for antibiotic resistance [15-17]. Although the spectrum of these indicators differ globally based on several parameters, the inappropriateness and the conclusions in relation to the development/burden of AMR is similar and even worst in the Nigerian context [29]. This study identifies amoxycillin, ampicillin/cloxacillin and metronidazole as the most frequently prescribed antibiotics in similarity to some outpatient settings but different from other hospital based studies which had cephalosporins, penicillin and aminoglycosides as the most common [20,26,27,29-31]. Availability of oral formulations which is favoured in community prescriptions may have been a major determinant in the general context but presence/use of guidelines in the more developed settings.

The unnecessary use of antibiotics in agriculture especially in animal husbandry has been identified as one of global threats to the fight against AMR [6]. Compared with the 20% for therapeutic use, antibiotic use in agriculture has increased up to 80% for prophylaxis and growth promotion [6]. With up to 18.3% of participants in this survey prescribing antibiotics to healthy animals and birds, it could probably be a tip of the iceberg and higher values may be obtained if larger scale studies are conducted. The concept of “on health” is now more than ever before required for a more holistic approach to addressing this global menace of AMR at all levels. This has been explored by a study in Nigeria with conclusion of a strong link between AMR and agriculture, which highlight the potential for worst situations if appropriate measures are not taken [14]. This study is limited to only CHEWs among all other healthcare workers and restricted to three states in Northern Nigeria. It has also not considered prescribers among veterinary health professionals and other members of the public who also consume antimicrobials. Additionally, the study used a convenience sampling method, thereby making it not generalizable. Implementation and improvement on existing legislation with continuous training and retraining of all healthcare workers on the dangers of antimicrobial resistance is paramount for better prescribing habits in Nigeria. There is need to establish and institutionalize antimicrobial stewardship programmes at all levels of healthcare delivery, both within the healthcare facilities and the communities. A “One Health” approach involving legislatures, regulatory agencies (such as PCN), law enforcement agents and the healthcare workers with concerted and harmonized efforts is likely an easy and realistic means of addressing this menace from the roots.

The context of AMR as a threat to patient safety has drawn the attention of the world as it continues to increase in magnitude especially due to rising effect of indiscriminate/inappropriate antibiotic prescribing. In developing nations, the burden is worsened by absent or inadequate regulations/guidelines with community settings being the worst compared to the hospitals. This study highlights some irrational antibiotic prescribing habits of primary healthcare workers with emphasis on the spectrum and indications for the various antibiotics prescribed. The high level of antibiotic use for wrong indications with background weak/non-functional regulations among the primary healthcare prescribers further buttresses the need for a more holistic approach in solving the problem of AMR in Nigeria and beyond.

What is known about this topic

- Poor antibiotic prescribing practices are major drivers of antimicrobial resistance;

- Multidrug resistant pathogens contribute significantly to the burden of HCAIs and poor patient safety indices;

- Improvement in antibiotic prescribing habits through implementing sound regulations and antimicrobial stewardship programmes using the concept of “one health” will ensure better patient safety at all levels.

What this study adds

- Primary healthcare workers constitute a major bulk of antibiotic prescribers in Nigeria;

- There are poor prescribing habits and suboptimal adherence to guidelines/regulations among CHEWs in northern Nigeria;

- There is need to strengthen antimicrobial stewardship programmes at primary healthcare levels as a major component in the fight against antimicrobial resistance.

The authors declare no competing interests.

MMM: Study conceptualization and writing of the draft manuscript, YM: Data collection, analysis and interpretation, SS: Data collection and analysis, MU: Data collection and analysis, ZY: Manuscript writing and review, AF: Study conceptualization, manuscript writing and review, AAA: Data interpretation, manuscript writing and review, MIS: Study conceptualization, manuscript writing and review. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

We heartily appreciate and acknowledge all PHC workers in northern Nigeria who participated and contributed to the success of this survey.

Table 1: some relevant survey questions as contained in the questionnaire

Table 2: spectrum of antibiotic prescribing among the respondents

Table 3: some possible indications for wrong antibiotic prescribing among the respondents

Figure 1: awareness, access and perception on adherence to available guidelines to antibiotic prescribing among the participants

Figure 2: perceptions of respondents on reasons for non-adherence to prescribing guidelines by PHC workers

- Maddy Pearson, Anne Doble, Rachel Glogowski, Stella Ibezim, Tom Lazenby, Ayda Haile-Redai et al. Antibiotic prescribing and resistance: views from LMIC prescribing and dispensing professionals. 2018.

- O´Neill J. Tackling drug-resistant infections globally: final report and recommendations. 2016. Accessed May 6, 2019

- Milani RV, Wilt JK, Entwisle J, Hand J, Cazabon P, Bohan JG. Reducing inappropriate outpatient antibiotic prescribing: normative comparison using unblinded provider reports. BMJ Open Qual. 2019;8(1):e000351. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Merrett GLB, Bloom G, Wilkinson A, MacGregor H. Towards the just and sustainable use of antibiotics. J Pharm Policy Pract. 2016;9:31. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Kotwani A, Holloway K. Trends in antibiotic use among outpatients in New Delhi, India. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:99. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Wise R, Hart T, Cars O, Streulens M, Helmuth R, Huovinen P. Antimicrobial resistance. BMJ. 1998;317(7159):609-610. PubMed | Google Scholar

- WHO. Antimicrobial resistance. In: global report on surveillance. 2014.

- Community health practitoners registration board of Nigeria (CHPRBN). National standing orders for community health officers, community health extension workers. 2015.

- Federal Ministry of Health Nigeria, World Health Organisation. National drug policy. 2005. Accessed June 23, 2019.

- Pharmacists Council of Nigeria. PCN´s approved patent medicines list. Accessed August 7, 2021.

- Pharmacists Council of Nigeria. Patent and proprietary medicine vendors (PPMVs) registration and licensing procedures and guidelines. 2019. Accessed August 7, 2021.

- Oyeyemi AS, Oladepo O, Adeyemi AO, Titiloye MA, Burnett SM, Apera I. The potential role of patent and proprietary medicine vendors´ associations in improving the quality of services in Nigeria´s drug shops. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):567. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Federal Ministries of Agriculture, Environment and Health. Antimicrobial use and resistance in Nigeria situation analysis and recommendations. 2017. Accessed June 7, 2021.

- Oloso NO, Fagbo S, Garbati M, Olonitola SO, Awosanya JE, Aworh MK et al. Antimicrobial resistance in food animals and the environment in Nigeria: a review. Nt J Env Res Public Health. 2018 Jun 17;15(6):1284. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Wasihun AG, Wlekidan LN, Gebremariam SA, Welderufael AL, Muthupandian S, Haile TD et al. Diagnosis and treatment of typhoid fever and associated prevailing drug resistance in northern Ethiopia. Int J Infect Dis. 2015;35:96-102. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Onyekwere CA. Typhoid fever: misdiagnosis or overdiagnosis. Niger Med Pract. 2007;51(4):76-79-79. Google Scholar

- Gwimile JJ, Shekalaghe SA, Kapanda GN, Kisanga ER. Antibiotic prescribing practice in management of cough and/or diarrhoea in Moshi Municipality, Northern Tanzania: cross-sectional descriptive study. Pan Afr Med J. 2012;12:103. PubMed | Google Scholar

- List of Nigerian states by population. Wikipedia. 2021. Accessed August 17, 2021.

- Cochran WG. Sampling techniques. New York. John Wiley and Sons Inc. 2nd ed 1963.

- Murphy M, Bradley CP, Byrne S. Antibiotic prescribing in primary care, adherence to guidelines and unnecessary prescribing - an Irish perspective. BMC Fam Pract. 2012;13:43. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Abdu-Aguye SN, Haruna A, Shehu A, Labaran KS. An assessment of antimicrobial prescribing at a tertiary hospital in north-western Nigeria. Afr J Pharmacol Ther. 2016;5(4):229-234. Google Scholar

- Llor C, Bjerrum L. Antimicrobial resistance: risk associated with antibiotic overuse and initiatives to reduce the problem. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2014;5(6):229-241. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Ogunleye OO, Fadare JO, Yinka-Ogunleye AF, Anand Paramadhas BD, Godman B. Determinants of antibiotic prescribing among doctors in a Nigerian urban tertiary hospital. Hosp Pract 1995. 2019;47(1):53-58. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Macfarlane J, Holmes W, Macfarlane R, Britten N. Influence of patients´ expectations on antibiotic management of acute lower respiratory tract illness in general practice: questionnaire study. BMJ. 1997;315(7117):1211-1214. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Kotwani A, Wattal C, Katewa S, Joshi PC, Holloway K. Factors influencing primary care physicians to prescribe antibiotics in Delhi India. Fam Pract. 2010;27(6):684-690. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Oduyebo OO, Olayinka AT, Iregbu KC, Versporten A, Goossens H, Nwajiobi-Princewill PI et al. A point prevalence survey of antimicrobial prescribing in four Nigerian Tertiary Hospitals. Ann Trop Pathol. 2017;8(1):42. Google Scholar

- Anyanwu N, Arigbe-osula M. Pattern of antibiotic use in a tertiary hospital in Nigeria. Eur J Hosp Pharm Sci Pract. 2012;19(2). Google Scholar

- Bozic B, Bajcetic M. Use of antibiotics in paediatric primary care settings in Serbia. Arch Dis Child. 2015;100(10):966-969. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Hashemi S, Nasrollah A, Rajabi M. Irrational antibiotic prescribing: a local issue or global concern. EXCLI J. 2013;12:384-395. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Chem ED, Anong DN, Akoachere J-FKT. Prescribing patterns and associated factors of antibiotic prescription in primary health care facilities of Kumbo East and Kumbo West Health Districts, North West Cameroon. PLOS ONE. 2018;13(3):e0193353. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Umar LW, Isah A, Musa S, Umar B. Prescribing pattern and antibiotic use for hospitalized children in a Northern Nigerian Teaching Hospital. Ann Afr Med. 2018;17(1):26-32. PubMed | Google Scholar