The recommendations for the implementation of the healthy workplace management model of the informal vendors

Maasago Mercy Sepadi, Vusumuzi Nkosi

Corresponding author: Maasago Mercy Sepadi, Department of Environmental Health, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg 2094, South Africa

Received: 30 Mar 2023 - Accepted: 05 May 2023 - Published: 05 Jul 2023

Domain: Environmental health,Work environment,Sanitation

Keywords: Street vendors, environmental health, management models, health, healthy workplaces, South Africa

©Maasago Mercy Sepadi et al. PAMJ-One Health (ISSN: 2707-2800). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article: Maasago Mercy Sepadi et al. The recommendations for the implementation of the healthy workplace management model of the informal vendors. PAMJ-One Health. 2023;11:11. [doi: 10.11604/pamj-oh.2023.11.11.39873]

Available online at: https://www.one-health.panafrican-med-journal.com/content/article/11/11/full

Research

The recommendations for the implementation of the healthy workplace management model of the informal vendors

The recommendations for the implementation of the healthy workplace management model of the informal vendors

&Corresponding author

Introduction: the current legislation and servicing of the informal trading sector is fragmented, resulting in inefficient use of limited resources. The present article is based on an original study that was carried out in the inner city of Johannesburg, which comprised risk identification and impact management using quantitative methods including the development of a healthy integrated workplace management model.

Methods: this article outlines the recommendations that support and seek to guide the local government in implementing the published model. The recommendations include the most effective control methods such as engineering controls and administrative controls and the least effective which is the use of appropriate protective clothing. The recommendations were presented using descriptive techniques, including the use of illustrations.

Results: stalls or markets should be planned in such a way that is equipped, safe and secure; moreover, sidewalks and parking areas are to be left unobstructed in order to guarantee that pedestrian traffic is not hindered. Air pollution sampling in trading areas is required, including trading markets and stalls, food carts, and vehicle exhaust monitoring. Primary healthcare services should be extended to markets to accommodate informal vendors. Furthermore, informal vendors should be given the knowledge and skills needed for improvement in their trade.

Conclusion: municipalities should restructure the current informal trading settings. Additionally, there is a need for rendering continuous services involving multi-sectoral departments and stakeholders.

The work processes and labour arrangements of informal workers, such as street vendors are mostly unregistered and unregulated and are excluded from governmental regulations and control [1]. In addition, most laws relevant to the formal sector during development make it difficult to adopt in the informal sector [1], including those pertaining to Environmental Health (EH) and occupational health and safety (OHS); and preventive steps to lower in-formal vendors´ workplace risks are frequently overlooked.

National laws usually exclude informal workers from their scope, even though international law upholds their rights to occupational health and safety protection [2]. The South African Department of Labour report (2020) indicated that although there is progress in health and safety matters in the country, the current legislation is fragmented and complicated, and it generally excludes the informal economy and domestic workers [3]. Furthermore, it suggested that the legislative review process be accelerated and that the South African Local Government Association (SALGA) support OHS systems and offer essential facilities for employees in the informal economy to promote OHS in the sector. The eThekwini Municipality's informal economy policy [4] is an example of this sector's advancement because it clarifies the local government's philosophy and guiding principles; it serves as the foundation for effective legislation; enables cooperation among various government agencies; serves as the basis for decisions regarding the allocation of resources for management and support; and it also serves as the basis for agreements with other stakeholders regarding what should be done.

The informal trading sector includes informal food vendors; and the requirements for this group are more than the ones for general informal vendors, especially in terms of legislation implemented by the Department of Health (DOH). The South African DOH´s mission is “To improve the health status of South Africans through the prevention of illnesses and the promotion of healthy lifestyles and to consistently improve the health care delivery system by focusing on access, equity, efficiency, quality, and sustainability” [5]. The services rendered by the DOH in South Africa include Municipal Health Services under the National Health Act, 2003 (Act No. 61 Of 2003) [6] which are enforced by Environmental Health Practitioners (EHPs). Part of the EHPs duties is food safety control which is supported by the enforcement of the Regulations governing General hygiene requirements for food premises, transport of food, and related matters (R638 of 22 June 2018) [7].

To support the changes required in this sector, a healthy workplace evidence-based model was developed [8] as one of the objectives of the study conducted in the inner City of Johannesburg (COJ) [9]. The management model was created to help with interventions in three areas of the informal vending business. Risks relating to the physical work environment were the emphasis of Part A, while risks relating to the knowledge, attitude, and behaviour (KAP) of the specific vendor formed Part B and the effects of that behaviour on their health were the subject of Part C [8]. The theme of the proposed integrated management model was to promote the three “S” secure, safe, and sanitary in trading places [8]. This present article seeks to recommend various methods, infrastructure and practices that can be adopted by local government; in the implementation of the proposed informal vendors´ workplace model [8].

Study design and setting: this article is based on a recent cross-sectional study that was carried out in the inner city of Johannesburg utilizing quantitative methodologies [8-13]. The study's informal vendor sample was drawn from the inner City of Johannesburg (COJ) Metropolitan Municipality [8], which has one of the highest rates of informal trading activity in South Africa [9,10,13]. The main study was conducted between March and December 2022 [12,13].

Participants and sample size: a total population sampling resulted in a sample size of 617 informal food vendors from 16 indoor (inside a building) and outdoor (street or roadside) informal vendor markets [12,13]. It consisted of (n = 338; 55%) indoor informal food vendors and (n = 279; 45%) outdoor informal food vendors [13]; and (n=7; 44%) indoor markets and (n=9; 55%) outdoor markets [11]. Any indoor and outdoor informal food vendors who were older than 18 years old and worked in designated daily markets made the inclusion criteria.

Data collection: the study adhered to the WHO's guidelines for human health risk assessment (HHRA) [14]. The HHRA was conducted by surveying the workplaces of indoor and outdoor informal vendors; identifying respiratory risk factors, measuring air pollutants, conducting interviews on respiratory health symptoms and diseases, and conducting a systematic review of the current environmental and occupational health statuses of these individuals [8-13]. Data collection tools included face-to-face questionnaire interviews on self-reported respiratory symptoms and diseases and demographical and operational matters analyzed with descriptive statistics from Statistical Package for the Social Sciences [13]; air pollution monitoring using GilAir pump for respiratory particulate matter [12], Radiello passive sampler was utilized to measure the NO2 and SO, and EXTECH air quality monitor for CO and CO2 and analyzed in a SANAS approved laboratory and Microsoft excel [13]. The integrated healthy workplace management model consisted of five major components: reviewing informal vendor legislation, reorganizing designated vending or trading sites, space allocation and occupancy, vendor training and skill development, and, finally, the sustainability of vending sites and vendors' health.

Recommendations development method: the recent study´s findings, current literature, and the components of the proposed model were used as the source of data to guide the development of recommendations or suggested solutions for the current problems faced by informal vendors. This stage is crucial to assist in ensuring multi-sectoral (Government, OHS, Environmental Health Professionals, and street vendors) responsibility for health and well-being [5]. This present article provides employers, vendors, or market managers with practical guidance on how to implement multiple layers of health risk mitigation strategies using the hierarchy of controls (elimination, substitution, engineering, administrative, proper protective equipment); a system used to reduce or eliminate exposure to hazards. The healthy workplace model developed [8] can be adopted by local governments in South Africa and implemented in phases. Descriptive methods were used to display the recommendations including the use of illustrations.

Ethical approval: this present article is a contribution to the first author´s Ph.D. study at the University of Johannesburg (UJ). The study was approved by the UJ (HDC-01-68-2021) and Research Ethics Committee (REC) (REC-01-141-2017). Additionally, it is it registered on the National Health Research Database (NHRD) (NHRD ref. no: GP_202102_036) and approved by the Health District Research Committee (DRC) (DRC ref.: 2021-02-013 The data gathering method used was anonymous, therefore the findings cannot be linked to any of the study participants.

Funding: this article is based on a study that received a supervisor-linked bursary from the University of Johannesburg (UJ) Faculty of Health and the UJ 2021/2022 Global Excellence Stature, Fourth Industrial Revolution (GES 4.0) Scholarship.

Formal management of informal trading activities: proposed phases of implementing the proposed healthy workplace model: there is a need for integration between all departments relevant to informal trading activities, external stakeholders, and informal traders or vendors. There is a need for reforms to the laws, the development of equipment that is suitable for the activities, and the expansion of occupational health and safety services into the trade. It is vital to have a multi-sectoral approach (new stakeholders, various government departments, informal workers' groups, unions, and other health professionals, in order to establish a more inclusive occupational health and safety [15]. Considering that it takes time to adopt new regulations and laws. Municipalities can begin implementing phases one to five of the proposed model while political institutions work on laws (Figure 1). The phases include; registration of all existing vendors; identification of sites, conceptualizing and designing trading markets and stalls; construction of markets and stalls; distribution and occupying of stalls; and continuous monitoring and service rendering.

Phase one: registration of all existing vendors: the first phase of implementing this model entails classifying and registering all currently operating vendors according to their trade categories (trading area and type of goods sold). Vendors should provide the necessary documentation at this phase to comply with registration criteria. This will guarantee that no vendor is overlooked during the process and that every vendor has the opportunity to fulfill the registration requirements. According to this data, all stakeholders will know how many informal vendors exist in each jurisdiction or address, how many sell what kinds of items (fresh fruits and vegetables, cooked food, clothing, or cosmetics), and how many have the paperwork required for registration. Classifying the informal vendors according to the goods sold will help the government in determining which types of stalls (infrastructure needs) are needed to accommodate which type of informal vendors. The data or statistics from this phase will enable the initiation of phase two.

Phase two: identification of sites and conceptualizing and designing trading markets and stalls: the local government, in collaboration with stakeholders, can provide street vendors in the city with sheltered food carts or stalls that meet their various needs such as the preparation of food and displaying and storing of their goods. The conceptualization and design of trading marketplaces and stalls inside the markets will be part of the second phase of bringing the proposed model into practice. The municipal departments were responsible for ensuring that informal trading activities are compliant should be involved in this rigorous stage, as should representatives or committees of the informal vendors.

Environmental Health is one of the departments that a municipality needs since it contributes to the infrastructure required for food vendors and the general hygiene standards for all other types of vendors. Economic development, EMS, the metro police's by-laws division, building, and town planning are more departments that will be required. The transportation station management will also be required, as many informal vendors do their business within transportation hubs, as well as the present traders managing agency and development and infrastructure departments, are additional government stakeholders required. As well, as support from knowledgeable external stakeholder groups would be essential at this stage. Examples of such groups include Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing (WIEGO) and similar organizations that have been investigating and promoting this trade in South Africa. In Bhubaneshwar, India, a group of eight elected members from the National Association of Street Vendors of India (NASVI) collaborated with town authorities (Bhubaneshwar municipal corporation and General government administration) to conceptualize and design the trading zone model [16]. The following is proposed for the completion of this stage: i) the committee should map the current trading locations and infrastructure around the city (whether designated or non-designated sites). Then decide whether sites are still appropriate for new trading markets; ii) find additional locations that have not been used previously but are appropriate for the activities of informal vendors. These locations could be abandoned structures, vacant lands, or any other suitable underutilized government properties. All outdoor locations should not hinder roadside vehicle parking and pedestrian walking pathways; iii) find areas where vendors who have their own complying carts can park during the day for trading and be provided with other essential services; iv) design the ideal market and stalls in accordance with applicable laws (national and municipal rules), such as R638 of 22 June 2018, for food stalls, and including the structure and equipment required for such activities. Further designing of generic informal vendor stalls in accordance with OHS-related legislation and building regulations, such as ventilation, lighting, and general water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) facility requirements. This stage should be accomplished through numerous meetings between the interested parties in order to create ideal healthy workplace markets and stalls. The concept can be discussed until an agreement is reached. Following the agreement, paperwork outlining the newly developed ideal informal vendors´ markets and stalls should be signed by all pertinent parties. It is also important to record the necessary departments' approval of the marker structure's design and internal layout of the sites and stalls.

Phase three: construction of markets and stalls: the outdoor vendors who are currently operating in locations without any kind of shelter should have prioritized in this phase. Upgrading or renewing the current suitable markets should come next in this phase. Then, as time goes on, all proposed and planned stalls should be constructed. The proposed design of trading stalls and infrastructure.

Ideal non-cooking vendor stall recommendations: the stalls or carts should be designed with the requirements of local government departments in mind, thus meeting the law and making it easier for the law enforcement process. These stalls' facilities may be reasonably priced for rental purposes. The stall recommendations are divided into two types: Movable carts for those street vendors trading along the sidewalk without any type of shelter (currently separated by paint marking), and Stationary stalls for street markets (currently in top-shelter stalls) [12]. Furthermore, the city can designate vacant stands or nearby building spaces as central storage areas where a specific group of vendors from specific streets can store their carts or goods and retrieve them in the mornings. However, if the government does not have space for storage, they can adopt the method implemented by the municipality of Bhubaneshwar in India by providing kiosks made up of strong iron sheets or secure material that cannot easily be damaged by environmental hazards which can be securely locked during non-operating hours for all outdoor vendor markets. The following illustrations can be used for designing such stalls/carts:

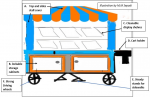

Sidewalk street vendors: Figure 2 depicts a movable cart that can be used by sidewalk vendors in Johannesburg streets such as Plein Street, where vendors trade in non-sheltered markets. These stalls should have (A) top and side covers, to protect against environmental hazards; (B) lockable storage cabinets for storing vendor equipment or foodstuff; (C) cleanable display shelves for displaying foodstuffs such as fruits and vegetables; (D) cart holder for easy usage when moving the cart to the trading site and from the central storage area; and (E) cart stand to keep the cart balanced when placed on the sidewalk. Finally, the cart should have strong wheels (F) for driving.

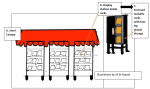

Street-market vendors: those vendors along the street market can use immovable, but secure, stall facilities. Figure 3 depicts stationary street markets and farmers´ market stalls that can be built at trading locations such as Johannesburg's Kerk Street market. These stalls can have (A) a steel canopy for environmental protection, as well as under that canopy (points A and B), enclosed and lockable racks with shelves inside for the display of goods. The racks will be supported on four legs. These stalls can accommodate more than three vendors, even five, under a single canopy that can be designed to fit the market's space; or as many stalls depending on the construction.

Ideal cooking vendors´ stalls (indoor and outdoor markets) recommendations: there is also a need for additional infrastructure for cooking food vendors, so it includes the following as illustrated in Figure 4.

Preparation and storage of food: preparation should not take place on or near the ground. It is recommended that food vendors practice good environmental and personal hygiene when preparing, packaging, and serving food to customers. Equipment and surfaces used in food preparation should be easily cleanable and preferably made of or covered with impervious materials. The stall shall have a stainless-steel preparation area (point F), hand wash basin and wash-up sinks (Point I), dry storage area or cabinets (point G), and a refrigerator facility (point H).

Ventilation: when cooking in poorly ventilated kitchens, the air vendors breathe can be harmful. As per the Building Regulations, Act no.103 of 1977, natural ventilation should be organized so that doors and windows relate to one another in such a way that the room will be effectively ventilated, and it should be at least five percent of the floor area of the room (or at least 0.2 square meters if the room is very small) [17]. The stall should have windows and a door (points A and C) that allow for cross-ventilation, as well as a customer stall window that is easily accessible (point B). The best way to ventilate the vendors' kitchen stall is to install a high-efficiency range hood or extractor fan above the stove and cooking equipment (point D). A qualified technician should inspect the gas stove for gas leaks and carbon monoxide every year [18]. According to system design, HVAC systems should be kept running in all enclosed trading trucks or canopy interiors to maintain thermal comfort and maximize outdoor air. If there are windows, it is necessary to use natural ventilation by opening the windows and doors to let more air in [19].

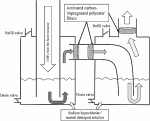

Food vendors urgently require health or hygiene education on the health effects of using unclean cooking fuel. In terms of reduction of emissions during cooking, small-scale commercial cooking workplaces, such as street food stalls, could benefit from smaller, simpler, and less expensive air pollution control filtration and absorption devices. Wu et al. (2021) conducted a study to design and implement a new cooking fumes collector which is displayed in Figure 5 [20]. Total aldehyde concentrations at the exhaust outlets of the original and new collectors were 342.2 and 80.8 g/m3, respectively, for stall A, and 622.7 and 283.1 g/m3 for stall B [20]. The corresponding concentration reductions for stalls A and B were 76% and 55%, respectively, and the emission rates were reduced by 91% (from 749 to 71 g/yr) and 76% (from 1,040 g/yr to 248 g/h). These results demonstrate the enhanced cooking fume removal capability of the novel collector, and the collector's high efficiency and low cost make it perfect for usage in small-scale commercial kitchens and food stands [20].

General infrastructure requirements: markets are to be provided with toilets and hand-washing facilities for informal vendors and clients. There is a need for the provision of portable hand-washing stations at the entrance and/or throughout the fixed-site markets. Street or sidewalks or roadside vendors should be provided with toilets and water facilities or located not far away from community water points. The provision of effective drainage systems is required at all types of markets for the disposal of wastewater.

Phase four: distribution and occupying of stalls: law enforcement officers and city council inspectors from each department, including building inspectors, EHPs, and EMS inspectors, should perform surveys and submit reports of compliance after the construction of markets and stalls. The department designated for stall distribution to informal vendors can commence the distribution procedure if the markets and individual stalls conform to national and local laws. The stalls will be distributed based on the results of Phase One and the types of activities or goods offered. Also, those vendors that qualified for the stalls and provided the necessary paperwork will be included. There must be stall registration documents provided to the vendors that certify their registration showing which addresses and for what function or trading activity. The informal vendors can now apply for licenses or permits such as trading licenses and certificates of acceptability for food premises where they submit the proof of stall registration and other necessary documentation in accordance with the department once they have been assigned a stall and given a document that proves stall registration. Then, the certificate or license that has been issued will be in the names of the vendors and the address of their stall, and it won't be transferable from one vendor to another or from one stall or location to another.

Phase five: continuous monitoring and service rendering: after informal vendors occupy stalls, each department will continue rendering its services. The development of monitoring strategies for the markets should be in place for continuous services to be rendered.

The Department of Health´s involvement in the management of informal vendors: the state should recognize the importance of EHPs in this paradigm and allocate additional resources to magnify the EH services offered to this industry in order to ensure that ongoing hygiene standards are maintained. The following are just a few of the responsibilities of an EHP that are administered in the management of informal vendors; Food facilities and foodstuff inspections; food, water, and swap sampling and analysis; and issuance of the certificate of acceptability (CoA) [7]; law enforcement; health education and promotion. The execution of these duties in informal trade necessitates manpower in addition to resources like financing for sampling and analysis because this department is already overburdened by the non-compliances with other types of businesses that they deal with on a regular basis. Informal food trading is one of the businesses that require a license in terms of Schedule 1 of the Business Act 71 of 1991 [21], currently in metropolitan municipalities such as the City of Johannesburg, the issuance of the license is within the DOH, environmental Health directorate [22]. This licensing should be incorporated within the model. The DOH should design a program of how the primary health care will serve the markets, this can be a scheduled visits program at the markets or a permanent mobile clinic closer to the vendors or randomly placed in town. A program of personal health services should be shared with the informal vendors especially if the government opted for scheduled visits to markets.

Air pollution management in informal trading

Regular air sampling programs in informal vendor markets: the work environment may be examined regularly by measuring the level of airborne pollutants and placing control measures where necessary.

Vendor carts/mobile trucks emissions control: the HHRA revealed the use of various cooking fuels by informal vendors, including cooking gas (45%) was the most common cooking fuel used, followed by electricity (13%), and open fire (11%), and 7% of the informal vendors used more than one type of fuel. In a study by Nahar et al. in 2020, it was found that food cart vendors typically use propane, charcoal, or both propane and charcoal for food preparation [23]. Depending on the fuel used for food preparation, there were observable differences in air pollution emissions in the area around the mobile food carts studied. The authors further suggested that the local air pollution law enforcement should incorporate regulating the activities of food cart vendors since the pollutants released during food preparation are typically released very close to breathing distances, degrade the interior air quality, and could be dangerous to human health [23]. The services should also include monitoring of air pollution, for example in sites or areas where vendors are trading with their own carts at open trading areas without municipal stall structures.

General roadside vehicle exhaust emissions testing: there is a need for change in air pollution management in urban areas as there is overcrowding of vehicles adding to air pollution problems in the cities. The Department of Transportation, the metropolitan police, and environmental management should assist in ensuring that air pollution from vehicles is reduced in support of informal trading healthy workplace program. To make sure that the exhaust gases emitted by any vehicle are within the authorized levels outlined by both national and international standards, vehicle exhaust emissions testing should be done [24]. The quantity of air pollutants released from a vehicle's exhaust is measured during an emission test [24]. This assessment will contribute to the reduction of pollutants that are bad for the environment thus contributing to better air quality in cities.

Health promotion and knowledge sharing: most often, informal workers and self-employed persons work in unsafe conditions or hazardous jobs without receiving the required safety and health training or knowledge. Various studies conducted on informal vendors have revealed a lack of adherence to proper protective equipment (PPE) [8-12]. The findings from the HHRA also revealed that improper respiratory protective equipment (RPE) (surgical and cloth masks) was used in terms of the impact of air pollutants such as particulate matter (PM) [12]. The monitoring of proper usage of protective clothing should be conducted in this sector. Since air pollution has been noted as a risk factor, environmental and occupational health professionals should advise vendors on the appropriate respiratory equipment that the vendors can use [8]. It was also noted that 75% of the trained vendors came from indoor marketplaces, primarily within the cooking category, suggesting that outside vendors are the group that is least likely to receive training. So, to ensure that the outdoor vendors are not left behind, it will be required that the programs designed for this trade be fairly distributed between indoor and outdoor vendors.

The general management of informal vendors´ activities or operations

Enhanced cleaning and disinfecting practices: food vendors should choose suitable disinfectants and food-graded cleaning agents while taking effectiveness and safety into consideration [19,25]. Vendors are required to keep their stalls tidy and to conduct all their business in a way that poses no threat to the public's health. A cleaning schedule, proper waste and waste-water management, and thorough cleaning of all facilities, storage equipment, and utensils are all required. Informal vendors, market managers, and environmental health professionals can create a standard operating procedure, a checklist, and regular training sessions for vendors on improved cleaning or disinfecting techniques. They should also keep track of when and how cleaning and disinfection are carried out [19,25]. Vendors should also encourage customers to wash their hands before and after eating.

Prohibition of sit-in areas at sidewalk trading sites: given the lack of infrastructure for dining and the informal vendors' proximity to the sidewalks, it should be prohibited for them to have client seating places.

Requirements at the point of sale: according to the World Health Organization (1996), stationary sales stations should be placed in an area with little to no danger of contamination by garbage, sewage, or other noxious or hazardous chemicals [26]. Food that is offered for sale should be appropriately covered and safeguarded from contamination if such hazards cannot be totally removed or controlled. If possible, use non-traditional payment processing and collection methods (such as having frequent customers place orders over the phone) to avoid physical interaction between staff and patrons and to shorten lines at the stalls with such little space.

General safety and security of informal vendors: the current study´s findings revealed that the majority of individuals who worked more than eight hours a day were vendors from indoor marketplaces, and it was discovered that indoor vendors were more inclined to take breaks during business hours; the security and safety of conducting business indoors may have made a difference; since outdoor vendors might not be able to leave their goods unattended during the day and may leave work earlier for the same safety concerns that may occur during the late hours of the day [12]. This new mapping and redesigning of markets and stalls should also solve the current security and safety issues as per the HHRA findings and provisions should be made for outdoor markets in terms of the availability of security personnel. The safety of vendors should not be compromised no matter the location they trade from.

Events vendors: the requirements for events vendors should be analyzed as much as daily trading vendors´ requirements. It is crucial that event catering vendors are registered and trained even if they conduct one-day events. Moreover, for those who use premises (e.g. stalls, kiosks, vendor transporting vehicles, trucks, carts) that have been inspected and certified by the EH department. Event organizers should avoid hiring vendors that are not certified. Some actions taken prior to the event may aid in accomplishing this goal. Special consideration should be given to potentially hazardous foods and their handling conditions; providing or arranging for supplies of such necessities as potable water, cold storages, and cooking fuels; providing conveniently located toilets and hand-washing facilities, even in the most basic form; and providing services for waste collection and removal, including disposable utensils, if used.

Prohibition of sit-in areas at sidewalk trading sites: given the lack of infrastructure for dining and the informal vendors' proximity to the sidewalks, it should be prohibited for them to have client seating places.

Requirements at the point of sale: according to the World Health Organization (1996), stationary sales stations should be placed in an area with little to no danger of contamination by garbage, sewage, or other noxious or hazardous chemicals [26]. Food that is offered for sale should be appropriately covered and safeguarded from contamination if such hazards cannot be totally removed or controlled. If possible, use non-traditional payment processing and collection methods (such as having frequent customers place orders over the phone) to avoid physical interaction between staff and patrons and to shorten lines at the stalls with such little space.

General safety and security of informal vendors: the current study´s findings revealed that the majority of individuals who worked more than eight hours a day were vendors from indoor marketplaces, and it was discovered that indoor vendors were more inclined to take breaks during business hours; the security and safety of conducting business indoors may have made a difference; since outdoor vendors might not be able to leave their goods unattended during the day and may leave work earlier for the same safety concerns that may occur during the late hours of the day [12]. This new mapping and redesigning of markets and stalls should also solve the current security and safety issues as per the HHRA findings and provisions should be made for outdoor markets in terms of the availability of security personnel. The safety of vendors should not be compromised no matter the location they trade from.

Events vendors: the requirements for events vendors should be analyzed as much as daily trading vendors´ requirements. It is crucial that event catering vendors are registered and trained even if they conduct one-day events. Moreover, for those who use premises (e.g. stalls, kiosks, vendor transporting vehicles, trucks, carts) that have been inspected and certified by the EH department. Event organizers should avoid hiring vendors that are not certified. Some actions taken prior to the event may aid in accomplishing this goal. Special consideration should be given to potentially hazardous foods and their handling conditions; providing or arranging for supplies of such necessities as potable water, cold storages, and cooking fuels; providing conveniently located toilets and hand-washing facilities, even in the most basic form; and providing services for waste collection and removal, including disposable utensils, if used.

The situation of informal vendors is vulnerable due to their lack of workplace infrastructure, access to clean water, and a lack of essential health care which may result in a risk to ill health. As per the Socio-Economic Rights Institute of South Africa (SERI)- South African Local Government Association (SALGA) (SERI-SALGA)´s informal trading recommendation report; the infrastructure required for informal trade should be provided by the municipalities and should create and make available comprehensive skill-development programs for informal vendors [27].

The implementation of the proposed healthy workplace model includes the involvement of various stakeholders and departments such as the Department of Health, building control, metropolitan police department, transportation department, and environmental management. This integration is for all departments that are currently involved in informal trading, and those who are required for the management of the current risk factors such as informal food premises that lack infrastructure, the air pollution caused by automobile emissions, and the current diseases related matters affecting informal traders which require the interaction of EH and OHS in the public health system. The integration of departments and integration of OHS in the health system will support the theory by Bamu-Chipunza (2018) who emphasized the significance of coordination between various governmental levels and the interplay of labor law with other policy areas, such as urban planning; acknowledging that different occupational groups and sectors in the informal economy such as street vendors face various health and safety hazards [2].

The researchers suggested forming a group to revamp informal marketplaces and market stalls in order to ensure compliance with relevant legislation. It suggested separating stalls into groups based on the products they sold, with food vendors' stalls being built in accordance with R638's 22 June 2018 specifications. Also, it suggested that legislation be developed to address the issue of air pollution caused by vendor carts and that the traffic department monitor vehicle exhaust emissions. Furthermore, it was advised that primary healthcare services be made available at marketplaces because vendors avoid going to clinics because of the long queues and potential income loss. It was also advised that more sustainable health and safety training be implemented to ensure that vendors understand their role in the new healthy workplace model, thus ensuring compliance with legislation, ensuring better sanitary conditions in their workplace, and wearing protective equipment.

According to the ILO's SafeWork Programme, it is possible and necessary to prevent occupational accidents and diseases in the informal economy by increasing public awareness and educating policymakers, municipal authorities, and labor inspection services [1]. Bamu-Chipunza (2018) further argued that in order to improve the working conditions for informal workers, awareness should start with health and safety specialists through training [2]. The various groups of workers in the informal economy should be included in the curricula of relevant training institutions, such as medical schools and environmental health training institutions. The improvement as per the recommendations will support the Sustainable goal (SDG); SDG 3.8 “Achieve universal health coverage, including financial risk protection, access to quality essential health-care services and access to safe, effective, quality and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all;” SDG 3.9. “By 2030, substantially reduce the number of deaths and illnesses from hazardous chemicals and air, water and soil pollution and contamination” [28].

Limitations: since this article recommendation is based on the results of an original study conducted in Johannesburg; the limitation of the main study was that air pollution monitoring was a baseline assessment with personal air sampling conducted on the maximum exposed groups with no control group and conducted on eight-hour working time. Furthermore, the respiratory symptoms and disease questionnaire was self-reported with no medical examination.

The recommendations made in this study are for the informal trading sector and will be required for better occupational settings, enhanced vendor knowledge and practices at work, and better vendor health. The crucial involvement of the DOH includes the extensive monitoring of informal food vendors. This function includes ensuring that food premises adhere to hygiene standards and that the handling, preparation, and storage of food is done in a way that prevents foodborne illnesses. This result and those of Hill et al. (2019) [29] have significant recommendations for general informal vendors and street food vending industries that will have an impact on the health and safety of vendors and their clientele. It is concluded that municipalities have a lot of latitudes to control informal trade within the confines of their municipal districts, and with that more work should.

What is known about this topic

- Informal traders (street vendors) are at an increased health risk due to various exposures such as air pollution exposure, lack of health and safety knowledge, and improper practices;

- Moreover, the current occupational settings of vendors are not conducive due to a lack of infrastructure and government services.

What this study adds

- Most industrial-developed models have not been documented in full in terms of how they can be implemented;

- This recommendation article seeks to expand in detail the implementation of the model developed for the informal trading industry.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Maasago Mercy Sepadi conceptualized the study and methodology. Maasago Mercy Sepadi collected data and wrote the original draft. Review and editing were done by Maasago Mercy Sepadi and Vusumuzi Nkosi. Both authors have read and agreed to the final manuscript.

The authors would like to acknowledge the University of Johannesburg’s research committees, namely the Environmental Health Departmental research committee, and the Faculty of Health Sciences Research Committee and Ethics Committee, for their comments and reviews during the drafting of the Ph.D. proposal development.

Figure 1: healthy workplace management model implementation phases flow diagram

Figure 2: sidewalk/roadside stalls: movable food cart for non-cooked food e.g. unprocessed crops, snacks, etc

Figure 3: market: immovable canopy built-in zones for fruits and vegetables

Figure 4: indoor cooking vendor (or food trucks) stall sketch layout

Figure 5: schematic diagram of a novel fume collector (Wu, Te-Cheng et al. 2021)

- International Labour organization (ILO). Informal economy: a hazardous activity. 2023. Accessed March 9, 2023.

- Bamu-Chipunza P. Extending Occupational Health and Safety Law to Informal Workers: The Case of Street Vendors in South Africa. University of Oxford Human Rights Hub Journal. 2018. Accessed March 9, 2023.

- South African Department of Labour. The Profile of Occupational The Profile of Occupational Health and Safety South Africa. 2020. Accessed March 9, 2023.

- Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing (WIEGO). eThekwini´s informal economy policy: Approved and adopted by the Durban Unicity Council. February 2002. Accessed 09 March 2023.

- South African Department of Health. National Department of Health Annual Report 2021/2022. 2022. Accessed March 9, 2023.

- South Africa Department of Health. National Health Act, 2003 (Act No. 61 Of 2003). 2003. Accessed March 9, 2023.

- South Africa Department of Health. Foodstuffs, Cosmetics and Disinfectants Act: Regulations: General hygiene requirements for food premises, transport of food and related matters. 2018. Accessed March 9, 2023.

- Sepadi MM, Nkosi, V. Strengthening Urban Informal Trading and Improving the Health of Vendors: An Integrated Management Model. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023 Mar 9;20(6):4836. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Sepadi MM, Nkosi, V. A Study Protocol to Assess the Respiratory Health Risks and Impacts amongst Informal Street Food Vendors in the Inner City of Johannesburg, South Africa. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Oct 28;18(21):11320. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Sepadi MM, Nkosi V. Environmental and Occupational Health Exposures and Outcomes of Informal Street Food Vendors in South Africa: A Quasi-Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Jan 25;19(3):1348. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Sepadi MM, Nkosi V. Working conditions and respiratory health of informal food vendors' in Johannesburg, South Africa: A cross-sectional pilot study. PAMJ-One Health. 2022;8(8):35158. Google Scholar

- Sepadi MM, Nkosi V. Personal PM2.5 Exposure Monitoring of Informal Cooking Vendors at Indoor and Outdoor Markets in Johannesburg, South Africa. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023 Jan 30;20(3):2465. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Sepadi MM, Nkosi V. Health Risk Assessment of Informal Food Vendors: A Comparative Study in Johannesburg, South Africa. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023 Feb 3;20(3):2736. PubMed | Google Scholar

- World Health Organisation (WHO). WHO Human Health Risk Assessment Toolkit: Chemical Hazards, second edition. December 8, 2021. Accessed February 23, 2023.

- Lund F, Naidoo, R. The changed world of work. A J Environ Occup Health Policy. 2006;26(2):145-154. PubMed

- Kumar R. The Regularization of Street Vending in Bhubaneshwar, India: A Policy Model. 2012. Google Scholar

- National Building Regulations, South Africa. National Building Regulations and Building Standards Act, 1977 (Act No. 103 of 1977). 1977. Accessed February 23, 2023.

- Califonia Air Resources Board. Indoor Air Pollution from Cooking. 2023. Accessed February 8, 2023.

- The American Industrial Hygiene Association (AIHA). Healthier Workplaces: Guidance for the Warehouse and Logistics Industry. 2021. Accessed February 8, 2023.

- Wu TC, Peng CY, Hsieh HM, Pan CH, Wu MT, Lin PC et al. Reduction of aldehyde emission and attribution of environment burden in cooking fumes from food stalls using a novel fume collector. Environ Res. 2021 Apr;195:110815. PubMed | Google Scholar

- South Africa. Businesses Act, 1991 (Act No. 71 of 1991). 1991. Accessed January 25, 2022.

- City of Johannesburg. Hawkers. 2018. Accessed February 23, 2023.

- Nahar K, Rahman MM, Raja A, Thurston GD, Gordon T. Exposure assessment of emissions from mobile food carts on New York City streets. Environ Pollut. 2023;267:115435. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Totalkare. Benefits of emissions testing. 2020. Accessed March 9, 2023.

- Global Food Safety Initiative (GFSI). Chemicals in Food Hygiene, Volume 2: Cleaning agents, sanitisers and disinfectants in food businesses: detection of traces and human risk assessment processes. 2019. Accessed February 6, 2023.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Essential safety requirements for street-vended foods. 1996. Accessed February 6, 2023.

- South African Local Government Association (SALGA). Towards recommendations on the regulation of informal trade at local government level. 2018. Accessed March 9, 2023.

- United Nations (UN). Sustainable Development Goals. 2015. Accessed January 25, 2022.

- Hill J, Mchiza Z, Puoane T, Steyn NP. The development of an evidence-based street food vending model within a socioecological framework: A guide for African countries. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(10):e0223535. PubMed | Google Scholar